One of the most expressive figures in contemporary Sakha art is Sveta Maksimova, a multidisciplinary artist working at the intersection of photography, video, performance, and object-based art. In her works, ancestral memory, corporeality, and spiritual aspiration intertwine into structures that create a space where personal identity and collective memory, cultural code and contemporary artistic forms meet. Maksimova’s projects demonstrate how the local traditions of the Sakha can be reinterpreted within a contemporary art context.

Originally from the Republic of Sakha, she consistently returns to themes of ancestral memory, corporeality, and migration, methodically combining the ritual symbolism of Sakha traditions with contemporary media practices. Her self-positioning as a representative of an ethnic group within a “post-imperial discourse” renders her works simultaneously politically charged and introspectively personal. She does not simply represent “sakhallyy” (Yakut), but reconstructs internal archetypes through movement, sound, and object.

Ije. Buor. Salgyn is one of Sveta Maksimova’s early projects, in which she translates the traditional concept of the soul’s threefold unity Ije kut, Buor kut, Salgyn kut into a contemporary visual-performative language. The project’s form is modular: a performance with the Serge object, video, a series of long-exposure photographs, sound improvisation, and a printed zine together generate a constellation of representations through which the traditional Yakut system of meanings is not cited directly but reincarnated. The work functions simultaneously as a ritual and as its document: the ritual as an embodied experience of local knowledge for the participants, the document as the medium through which this knowledge is transmitted into the sphere of contemporary art.

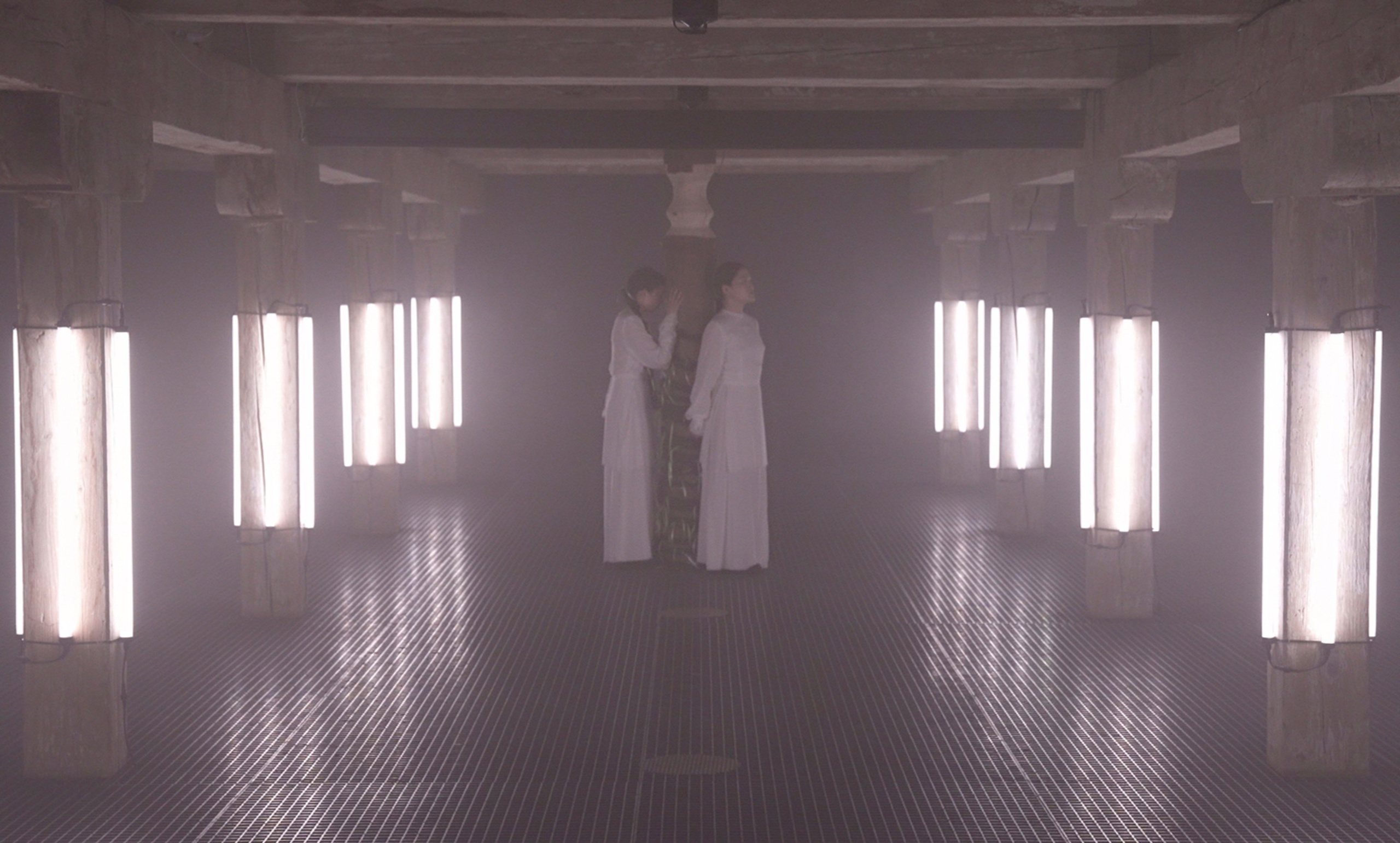

Ije. Buor. Salgyn clearly articulates the concept of the Kut Sur triad. The central symbol the wooden pole, Serge acts as an axis of the world and of lineage. It anchors memory and serves as the material bearer of Ije kut. Around it unfolds the performance: two young women enact a cyclical movement, braiding their hair into the “roots” of the pole and undertaking a monotonous ascent. This bodily action constructs Buor kut, the earthbound, physical side of the soul flesh, labor, touch, connection with wood and landscape. Maksimova notes that the “twisting” around the Serge symbolizes the cyclicality present in everything: in history, in life, in nature.

Voice and the sound of the khomus fill the space with vibration an embodiment of Salgyn kut, the striving, the intellectual and spiritual movement. This ritual element sets the structure of the performance, binding the three worlds spiritual, earthly, and ancestral into a unified performative system. During the performance, the women, interacting with the Serge, become fixed to it, creating a visual image of the impossibility of complete release and of the irreversible interconnectedness of sitim. The text that emerged parallel to the preparation for the performance reflects the artist’s personal sensations linked to migration, historical events, and experiences of collective memory. It does not correspond directly to the bodily actions of the participants but rather creates an emotional and intellectual backdrop.

Sveta Maksimova questions who may be considered a bearer of culture and whether one can be a bearer if the language and traditions have not been fully mastered. She recounts her own experience: Born in the Republic of Sakha, yet Russian was her first language; her family background was mixed, including Russian and Chuvash roots, which produced a syncretic understanding of culture. She began learning the Sakha language only after the death of her grandmother, who herself was a Russian-language speaker. Unlike her younger siblings, for whom Sakha became their first school language, for the artist, cultural knowledge had always remained something observed and studied, rather than fully internalized as lived practice.

An important part of the project is the disappearance of the performance’s central object, the Serge. The artist recounts that the object “simply disappeared” when she intended to preserve it for future performances: “The Serge simply vanished from the space where I was studying. I began asking, where is my heart, where is my tree… Eventually it turned out that it had simply been taken away, and we could not locate it, though I made every effort.” Despite personal distress and emotional reaction, she perceives this event as a natural continuation of the project rather than an accident. According to Maksimova, in traditional Sakha culture, “you cannot and must not possess” objects of sacred significance. She reflects on her initial desire to store the object, calling it an expression of ego: “I just wanted to keep it. But a Serge is not created to be kept.” Here emerges a conflict between individual artistic control and the traditional logic of the object as part of the natural and spiritual environment. The disappearance becomes not a loss but a ritual act, symbolizing the necessity of respecting the cultural and natural sphere.

Conceptually, the event expands the narrative of Ije. Buor. Salgyn: it incorporates unpredictability, chance, and an ethical dimension into the project’s very structure. It becomes an artistic act that heightens the emotional and spiritual dimension of the work, which registers the impermanence and non-ownership of cultural heritage. It transforms the interaction with the object into an ongoing process in which the tripartite perception of the soul (Ije kut, Buor kut, Salgyn kut) is simultaneously visualized and emotionally experienced by the artist herself. Sveta Maksimova concludes: “The disappearance of the object is a metaphorical continuation of the ritual, a key artistic moment that underscores that culture and tradition are not fixed in static forms they are in motion, in constant reflection. I had no right to appropriate it and simply keep it, depriving the Serge of the possibility of remaining in dialogue.”

The very process of creating Ije. Buor. Salgyn can be regarded as an independent artistic act, where each stage from working with the object to interacting with the body and with language becomes part of the structure. The central object of the project, the wooden pole Sérgä, was acquired by the artist as a long log. After carefully studying what a true Serge should be, she created it with respect for the tradition. An integral part of the project is the bodily realization of the idea the creation of costumes and the interaction with the body. Sveta Maksimova sews the traditional white dresses, khaladaay, herself, and uses long artificial hair (up to 20 meters) symbolizing salama, the ritual ribbon of the Sakha people, braided from white and black horsehair and adorned with offerings to the spirits. Salama serves as a “bridge” between humans and spirits and is used in purification rites.

Work with language and cultural identity held particular significance for the project. At one point, Sveta’s mother told her: “You do all these projects because it benefits you. You don’t know the Yakut language why are you even doing this?” This sentence became an important reference point for the artist, who understands herself as Sakha. It pushed her to reflect more deeply on her practice, on her right to speak about the culture, and on the responsibility of representing it. Maksimova asks: who is a bearer of culture? Can she be a bearer without mastering the Sakha language perfectly? As a result, she devoted considerable time to rehearsing the pronunciation of Sakha words; in the final performance, I noted that the words sounded almost professional, as if spoken by a trained actress. This stage became for her a ritual inclusion of the Sakha language into the artistic act, uniting bodily, material, and sonic dimensions into a single model.

It is important to emphasize that Ije. Buor. Salgyn does not strive for ethnographic accuracy. It is rather an artistic reconstruction of memory a “practice of restoration” in which, through her own experience and inner processes, the artist examines how cultural integrity is preserved and transformed. The work demonstrates that the traditional concept of the soul’s threefold unity can be not only part of a sacred worldview but also actively used in contemporary artistic discourse.

I first encountered Ije. Buor. Salgyn in Paris, at the exhibition of artists from Russia’s small Indigenous peoples Proof of Existence, organized by the collective Corooted at Galerie L’Aléatoire. For me, it was a subtle moment: Maksimova’s work, like the works of other Sakha artists, created a space in which I suddenly felt an internal return to myself. Amid these works, the everyday noise dissolved, and within me awakened that Sakha sensation of the world that sometimes fades when one is far from their native land.

GLOSSARY

Iye kut.

Cultural needs. Spiritual needs: the need for unity with the national spirit; the spirit of the native land; the ancestral faith (Popova G. S.).

Salgyn kut.

Integrative informational and communicative needs: the need for audio information; for video information; for communication (Popova G. S.).

Buor kut.

Biological needs. Physiological needs: for food; for the alternation of sleep and wakefulness; for procreation (Popova G. S.).

Serge

A traditional Sakha hitching post, a sacred wooden pillar symbolizing the connection between a person, the land, the lineage and the celestial world; its installation was accompanied by rituals and regarded as an important element of the spiritual culture of the Sakha people.

Khomus

A traditional Sakha musical instrument of the jaw harp type, producing a vibrating overtone sound and used in both everyday life and shamanic practice.

Salama

A traditional Sakha ritual pendant made of multicolored ribbons, used for protection, for bestowing blessings, and for addressing guardian spirits; it is hung on trees, sierge posts, or in sacred places.

Aal Luuk Mas

Interpreted as the material embodiment of the World Tree in contemporary Sakha culture. In tradition, it symbolizes the axis of the three worlds and embodies the cognitive, normative and value dimensions of Olonkho cosmology.

LITERATURE

Xenofontov, G. V. Shamanism. Selected Works. Yakutsk: Creative Production Firm “Sever-Yug”, 1992. 315 p.

Popova, G. S. “Aal Luuk Mas, the World Tree, in Contemporary Yakut (Sakha) Culture.” Values and Meanings, 2019, no. 4 (62), pp. 103–120.

Popova, G. S. The Triune Essence, Human Needs and Theories of Culturogenesis. Yakutsk: Institute of Languages and Culture of the Peoples of the North-East of the Russian Federation, North-Eastern Federal University named after M. K. Ammosov.

Popova, G. S. The Triunity in the Spiritual Culture of the Ethnos: Monograph, ed. by E. P. Borzova. St. Petersburg: Asterion, 2009.

Nature mystique

Ecology of the Soul: Kut-Sür in the Visual Practice of Yen Sur.

Ayar Kuo, between two worlds: the memory of a people in images